If one is miserable enough to be tracking the trajectory of Greek manufacturing production she/he may have noticed that after a headfake in late 2012 – early 2013, when the 6-month moving average of the manufacturing production index slipped into positive territory, it dipped right into the abyss again.

If someone adds the respective indices for

Spain, Portugal and EU28 into the mix one thing that becomes eerily obvious is

that at the same time that all others rebound, we plunge.

|

| source: Eurostat, own calculations |

An easy conclusion out of that would be that

Greek manufacturers, despite the collapse in domestic demand, remain

desperately inward-oriented. Some others would claim that the lack of financing

or high energy cost (both prevalent stories in Greek mainstream media) is to

blame. Usually though truth lies somewhere in the middle. But we’ll come back

to that later.

If one takes into consideration the fact that

aggregate indices can conceal huge divergences among their components, a good

question would be if the spike of the manufacturing production index observed

earlier this year was even an actual spike or if it was driven by a few

index-heavy sectors while the underlying conditions was still dire. If that was

the case then the fact that production plunged again should be no surprise.

I think that a relatively straightforward way

to gauge this is to find out how many sectors where in expansion each month

(disregarding for now the different weight that different sectors may have).

The total number of sectors in this classification is 15. I think that

comparing the situation in Greece with that of Spain and Portugal would help us

to draw some conclusions but since data for Portugal were spotty, we have to do

with just Spain (re Spain, the last couple of months, namely Oct and Nov a couple

of sectors lacked data but that doesn’t alter the conclusion-reaching here).

Here is the chart.

|

| source: Eurostat, own calculations |

Manufacturing in Spain was in expansion on

September and November of 2013, while in Greece in August, October and December

of 2012, as well as March, April and June of 2013. Common sense has it that

during the first few months of expansion the sector will be dragging its feet

out of recession with fewer sub-sectors on the rise while the expansion will pick

up pace as and if the rise in production persists. True to that, in Greece,

more sectors were in expansion in 2013 than 2012 but they were still far fewer

than those in the very first months of the rebound in Spain. Meaning, in my book,

that Greek manufacturing cannot be said that it was in expansion these months

but that it was merely trying to form a base and stabilize (and not with

particular success as it appears).

I think it’s time to come back to the question

I posed earlier in the post. Why can’t Greek manufacturing catch a break?

One reason cited often enough is the lack of

financing. The DG ECFIN survey about Industry offers some insight on that.

|

| source: DG ECFIN |

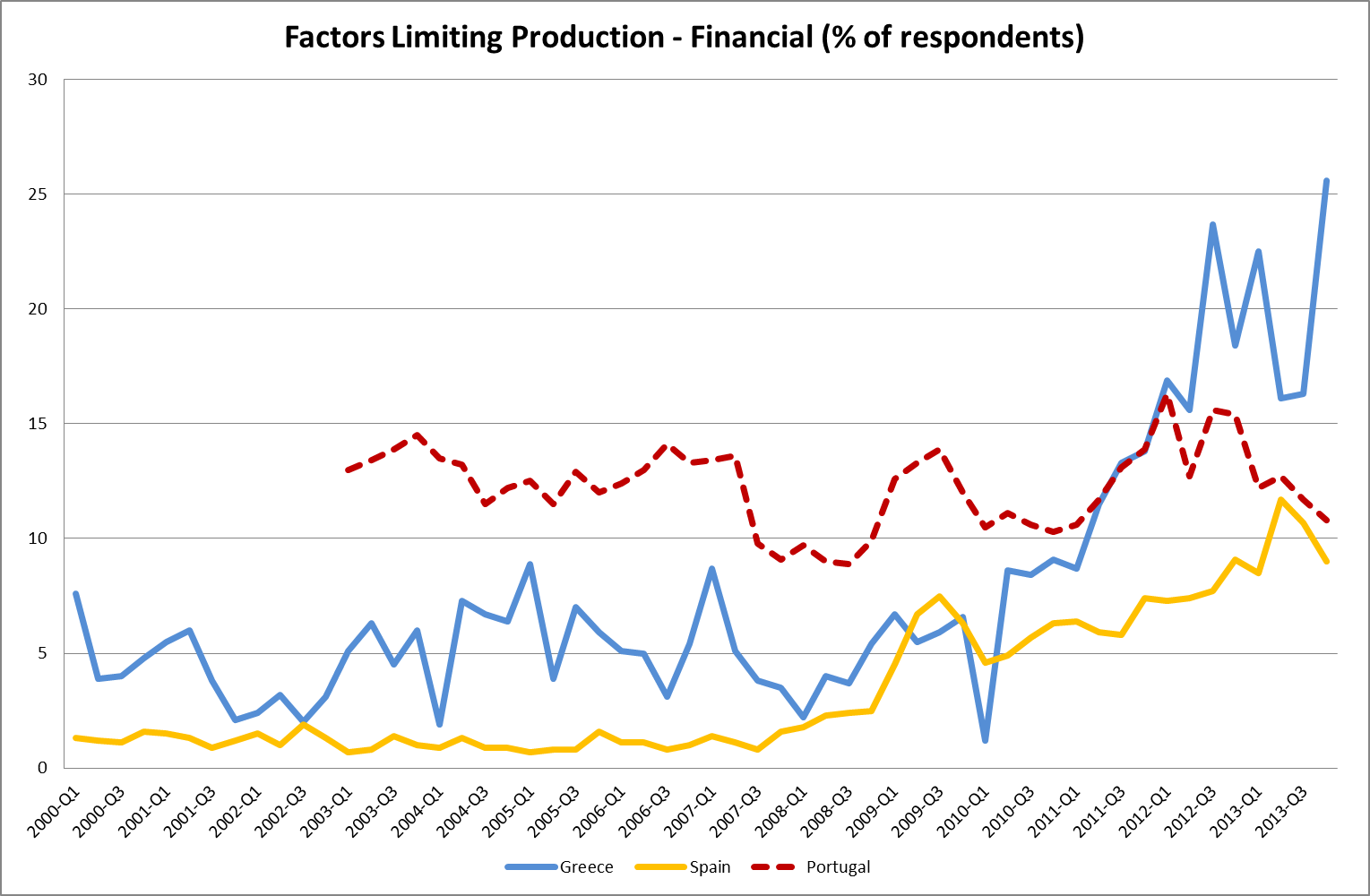

The % of respondents citing financial problems

as the main reason limiting production is rising fast in Greece, at the same time

when it appears to be dropping in Spain and Portugal. So that argument holds

some water.

At the same time the % of respondents choosing

another answer to the very same question is rather interesting.

|

| source: Eurostat, own calculations |

|

| source: DG ECFIN |

The Spanish and Greek manufacturing sectors

have suffered an almost equal collapse when compared to the 2008 level but the

% of Greek firms participating in the survey who claim that they are happy with

the present situation is considerably higher than the respective figure for

Spain. Could this mean that a sizeable

chunk of Greek manufacturers are still happy with just shooting for the

internal market?

Another problem often cited in Greek media are

high natural gas prices and especially for firms in the highest consumption

bracket.

Natural gas prices for top-bracket consumers in

Greece are indeed among the highest in the EU28. So we can chalk up one more

obstacle in the Greek manufacturers’ quest for survival.

|

| source: Eurostat, own calculations |

The reason that this is the case though is not

the tax burden as it is widely believed but rather the net natural gas prices

that Greece is charged with. What room is there for these to be adjusted

downwards through re-negotiation is anyone’s guess.

Time to wrap this up. Mainstream media pepper us

with various reasons why Greek manufacturing cannot catch a break. Some of

these are legitimate and others should be taken with a pinch of salt. It always

comes back to a couple of facts though, the adjustment process has started off a very low base and a change in mentality is badly needed and this is

where adjustment is even slower, if any.

P.S. It is interesting to add a little twist to

the debate about natural gas prices that Greek manufacturers are charged with. The

lower a country’s produce value added component is the more adverse the impact

of gas prices charged.

|

| source: Eurostat, own calculations |

Considering the multiple of headline

productivity figure for Greek manufacturing to the price for top-bracket natural

gas consumers, Greece falls to the middle of the relative table. Using that

yardstick, the most expensive natural gas on that basis is paid by Portugal.

(I know that this is a very crude measure and

given the financial stress that Greek firms are under it may underestimate the

impact of natural gas prices paid but it still is significant).